What’s needed to build interconnectors for Southeast Asia’s energy transition?

6 min read 1 October 2024

Southeast Asia can harness regional interconnectivity as a critical energy transition capability. With a 60-year head start on the politically and financially challenging task of building interconnectors, the European experience offers important guideposts for governments and investors.

To solve the trilemma of affordable, green and secure energy, many of the nations in Southeast Asia are making bold moves, with diverse strategies depending on each renewable resource’s availability, landmass and stage of economic development.

For example, the geographically small and renewables constrained Singapore has increased its ambition for renewables imports from 4 GW to 6 GW by 2035. In contrast, with more than 350 times Singapore’s landmass, Laos seeks to become the ‘Battery of Southeast Asia’ by exporting its hydropower to firm intermittent renewables like solar and wind – similar to the role Norway’s rich hydro resources play in Europe.

No matter what the strategy in play, all nations in the region have made moves towards more networked interconnections and the necessary infrastructure to support cross-border power trading. To achieve its target 6 GW of imports, Singapore is seeking to build subsea interconnectors from Indonesia and Sarawak. Meanwhile, Laos is continuing the development of several new overland interconnectors, including with Vietnam and Cambodia. Singapore has also recently announced expanded electricity imports via Malaysia. The ambitious Australia-Asia Power Link, which includes a subsea cable route through Indonesian waters, seeks to harness and store renewable energy from one of the world's most reliably sunny places – Australia’s Northern Territory – for 24/7 transmission to Darwin and Singapore.

Global mega trends are giving nations with plentiful renewable resources ever greater incentives to commercialise these assets. Net zero targets, electrification, urbanisation and the growth of power-hungry data-centre infrastructure spurred by digitalisation trends and AI are combining to create an exponential increase in demand for clean energy.

Multiple advantages to regional interconnectivity

As the region’s economies decarbonise, a much larger and greatly enhanced regional electricity network can confer a strategic advantage to ensure both reliability and efficiency. Interconnection is the key to getting power, particularly renewable energy, from where it is produced to where it is needed.

A well-designed interconnection network will improve grid stability and drive down energy costs by allowing the region to balance supply and demand over larger geographical areas and smooth resource availability. While solar resources are relatively abundant in most of Southeast Asia, other renewable energy resources are unevenly distributed across the region’s archipelago, with the greatest potential for:

- Hydro resources in East Malaysia, Cambodia and Laos.

- Wind resources in the mountainous areas of Thailand, the Philippines and the coastal areas of Vietnam.

- Geothermal resources in Indonesia and the Philippines.

- Bioenergy in the agricultural sectors of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand.

Cross-border power trading will help countries both address intermittency challenges and extract economic efficiencies. Hubs in the regions are expected to emerge with more interconnections between countries and multiple markets interacting, making the overall system resilient and dynamic.

Interconnection will also incentivise investment in large-scale power projects and associated network infrastructure that may not otherwise be viable at the national level, especially for smaller, resource-rich countries with relatively small internal electricity demand. New transmission will also be needed to overcome in-country geographical challenges, such as Vietnam’s struggle to connect its solar resources in the south with power demand in the north.

The International Energy Agency estimates that an overall grid investment of approximately US$21 billion annually will be needed across the region from 2026 to 2030 to enhance electricity interconnectivity.

Europe’s multi-decade journey offers important lessons

Europe has been building and commissioning interconnectors since 1961, when the Cross Channel HVDC scheme between UK and France became the world’s first cross-border subsea power interconnector. This project consisted of a 64 km subsea cable, with a capacity of 160 MW. Fast forward through more than 50 years of increasingly sophisticated interconnection projects, and one of the latest additions to the European interconnector network is the Viking Link between UK and Denmark. This 768 km subsea cable has a capacity of 1.4 GW.

These and many other interconnectors facilitate power trading in Europe, allowing the transport and movement of large amounts of electricity depending on where resources are most abundant, and demand is the greatest.

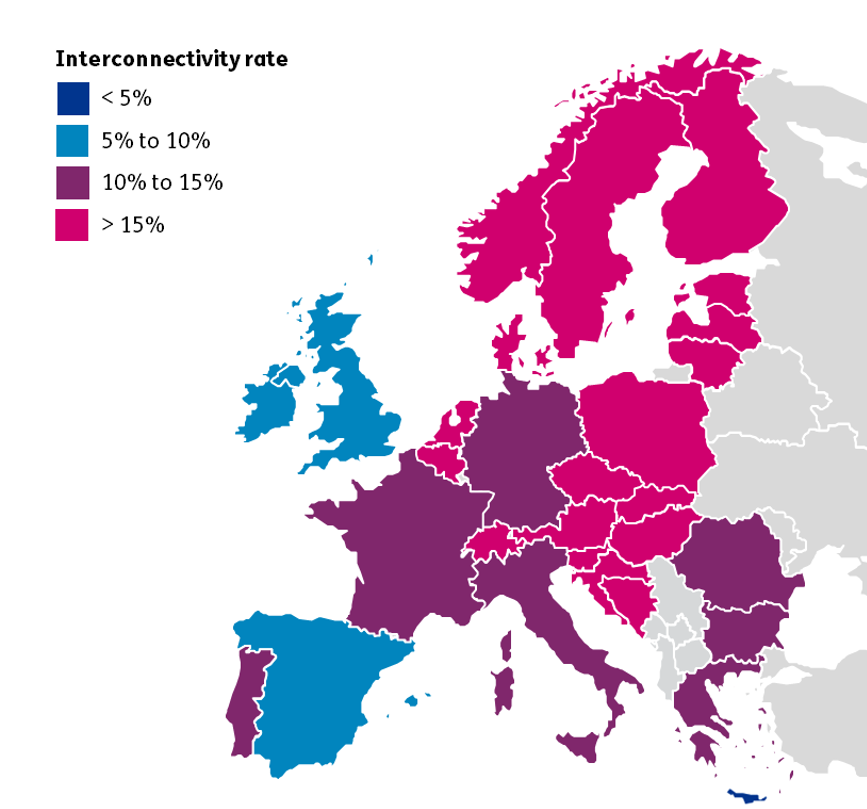

Interconnectors are recognised as being essential for Europe’s energy transition. The European Union (EU) has set a target for EU countries to connect 15% of their installed electricity capacities via interconnections by 2030.

What can Southeast Asia draw from the European experience?

Interconnection will be driven by bilateral agreements at the start

Successful interconnector projects require robust collaboration among countries and their respective grid operators. Effective coordination is essential for efficiently managing the complexities of cross-border electricity flows supporting common operational standards and regulations. Close coordination can also reduce the overbuild of grid infrastructure. In an ideal world, cross-border energy trading and interconnection development would occur within a common, universally accepted, regional legal framework, providing investors with certainty. However, in reality, that is not what occurred in Europe. The first European interconnector was built at a time when Europe was by no means united – 30 years before the EU was created.

In fact, European interconnections depended on the type of bilateral agreements already in play in Southeast Asia. Further, another good example would be the multiple energy cooperation Memoranda of Understanding between Indonesia and Singapore to facilitate cross-border trading projects and interconnections, and investment in Indonesia’s renewable energy manufacturing industries. Bilateral agreements like these provide the building blocks for a more integrated, regional grid.

The key takeaway is that interconnector projects can be initiated based on current operating constructs, with a view towards more harmonised policies and standards that may be put in place in the future.

Certainty is the biggest incentive

Interconnector projects, by definition, involve collaboration between two or more countries, adding a unique level of complexity. They come with inherent project risks, which include technical complexities, long construction lead-times, evolving regulations and potential uncertainties in revenue streams. In particular, the extended lead time for projects means that market conditions (policy, regulation, market design, counterparties) could look very different by the time a project is finally completed and the asset is ready for operation.

Historically, European interconnector projects have been financed primarily by Transmission System Operators – and stable and predictable national regulatory frameworks are needed to secure project financing and attract private investment. Governments should bear in mind that, when it comes to investing in energy transmission projects, certainty is more valuable than subsidies.

Real-time price signals can enhance economic efficiencies

Real-time price signals can provide the economic incentives for grids to use the lowest cost resource available. This has been the case in Europe’s integrated electricity market, with power flows being directed by where the need is the greatest, and from where supply is most abundant. This is not yet the case in Southeast Asia, given that most of the grids primarily operate on a single buyer basis, with limited electricity spot or merchant market exposure. However, there is value is developing the pathways towards such power trading arrangements, which can allow for significant economic efficiencies to be gained.

Recognising the different levels of economic integration across Southeast Asian nations as compared to countries in Europe, it is clear that not all policies and lessons can be directly applicable.

It will eventually require a concerted effort and bold visionary political action by regional governments to create an environment that accelerates the transition to an interconnected energy future. The key is to get started and create a clear framework that gives investors the confidence to make large-scale infrastructure decisions, helping to build interconnectors and a more connected energy grid.

At Baringa we help our clients shape their decarbonisation strategy, secure their energy needs, invest in future energy technologies and capture energy transition market opportunities.

For more insights, reach out to our team.

Our Experts

Related Insights

Organisational agility: a guide to taking the first steps

Our business agility and operational excellence expert Simon Tarbett offers some advice to clients when asked the question, Where To Start?

Read more

The need for agility to grow revenue and thrive in a turbulent market

We’re looking at how organisations need to be agile if they’re to grow revenue and thrive in a turbulent market.

Read more

How to set targets to drive business performance

Targets are essential for driving better business results. Let’s discuss what companies should – and shouldn’t – be doing.

Read more

How frozen organisations can become fluid

To develop organisational agility, focus on being like water.

Read moreIs digital and AI delivering what your business needs?

Digital and AI can solve your toughest challenges and elevate your business performance. But success isn’t always straightforward. Where can you unlock opportunity? And what does it take to set the foundation for lasting success?